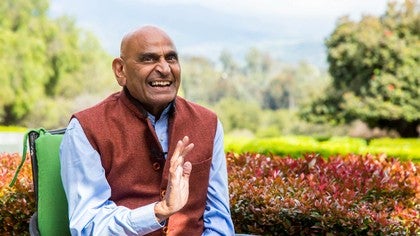

[Article sourced from Sri Ravi Ravindra's website: www.ravindra.ca]

In the Yoga Sutras 2.2 Patanjali states that the practice of yoga is for the purpose of cultivating samadhi and for weakening the kleshas (hindrances or obstacles).1 The various hindrances (kleshas) are ignorance (avidya), the sense of a separate self (asmita), attraction (raga), aversion (dvesha), and clinging to the status quo (abhinivesha).

One common lesson of all the scriptures and the teachings of the sages is that if I remain the way I am, I cannot come to the Truth or God or the Real. A radical transformation of the whole of my being is required. And a basic requirement of that transformation is freedom from my usual self, conditioned by all the social forces driven by fear and desire arising from self-centredness. Christ said, “He who would follow me must leave self behind” (Matthew 16:24). We see in the Yoga Sutras 3.3, “Samadhi is the state when the self is not, when there is awareness only of the object of meditation.”

Samadhi is a state in which the ‘I’ does not exist as separate from the object of attention. It is a state of self-naughting, the state spoken of in Buddhism as akinchan, a state of freedom from myself or a freedom from egoism. There is no observer separate from the observed, no subject separate from the object. Samadhi is a state of consciousness in which there is a non-fluctuating and steady attention so that the seeing, the seer, and the seen are fused into one single ordered whole.

In samadhi seeing is without subjectivity. Attention in the state of samadhi is free attention, freed from all constraints and all functions. Attention in this state is not conditioned by any object, even subtle ones, such as ideas and feelings. Only knowledge gained in such states of consciousness can be called objective in the true sense of the word; otherwise, it is more or less subjective.

Avidya (ignorance) is the cause of all the other obstacles; it is defined as “seeing the transient as eternal, the impure as pure, dissatisfaction as pleasure, the non-Self as Self.” (Yoga Sutras 2.5). In the heart of the Indian spiritual traditions, ‘koham?’ (‘Who am I?’) is considered the fundamental inquiry because in general we identify ourselves with the non-Self and take it to be the Self. According to all the sages in India, the basic source of our human predicament is ignorance of our own true nature. Everything else follows from this. “Avijja parmam malam (ignorance is the great blemish),” is a remark of the Buddha in the Dhammapada. It is in ignorance that we mistake the transient for the eternal, the unsatisfactory as satisfactory, and the non-Self as Self. This leads to illusion, conflict, and suffering, to be free of which is the aim of yoga.

Since the root cause of the problem is ignorance, naturally, the solution is real knowledge (jnana). This knowledge is of a radically different kind than scientific or philosophic or scriptural knowledge. There are several words to refer to this special kind of knowledge: vidya (cognate with the English ‘video’, to see); jnana (cognate with ‘gnosis’); bodhi (the root, budh, of this word is the same as in ‘buddha,’ awake and discerning); prajna (insight). This insightful and direct perception is possible only when the mind is in samadhi. When the hindrances to the state of samadhi are removed, true insight into the nature of reality results.

The first outcome of avidya is asmita which is defined as the misidentification of the power of seeing with what is seen (Yoga Sutras 2.6). Asmita is the illusion that I am a separate self, isolated from the Whole, with my own ego-centered projects.

Asmita literally means ‘I am this’ or ‘I am that,’ thus separating the small self from the entire vast reservoir of Being, from Brahman (literally, The Vastness). The Self says ‘I AM’—as in the very grand sayings of Christ, when he is in the state of oneness with Yahweh (which in Hebrew means ‘I AM’). “I AM is the way and the truth and the life” (John 14.6). Ego says ‘I am this’ or ‘I am that,’ thus attaching itself only to a small portion of the Vastness.

Asmita is the result of the misidentification of the power of seeing, which is Purusha (or Atman), with what is seen, namely ‘body-mind.’ The isolated self regards the vehicle (body-mind) as the real Self. In the movement from asmita (I am this) to Soham (I AM), from a limited self to the Self, from the identification with the body-mind to oneness with Purusha, the right order is discovered. The resulting insight is naturally full of truth, love, and joy.

It is important to remark that to be free of our attachment to the small self, or the ego, does not mean to be against it. Ego also has its place; it can be a good instrument when engaged in the service of the Self. Ego can be a good servant but disaster results when it becomes the master. When I am not connected with the Self or the Real I, ego takes over. As a Chinese classic puts it, “When the lion is departed from the mountain, the monkey becomes the king.” The subtle shift in the meaning of asmita from Sanskrit where it is close to ‘self-assertion’, to Hindi, where it is close to ‘self-confidence’, is a reminder of the need to find the right place of the ego.

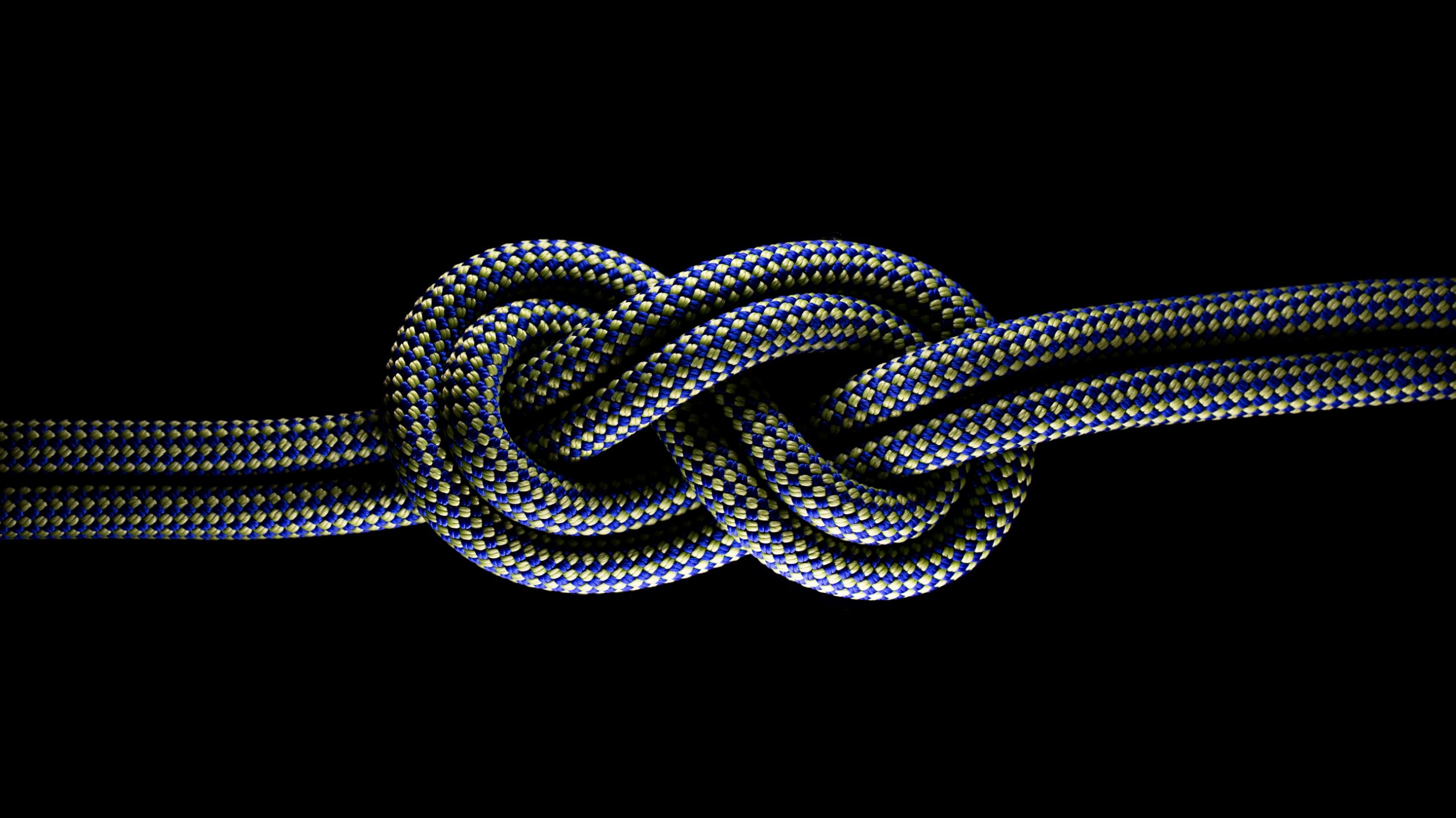

The other obstacles are raga and dvesha. Raga is the attachment to pleasure; dvesha is the attachment to suffering. The natural tendency to wish to relive pleasurable experiences is understandable, but it is particularly odd that we are more attached to our suffering than to our pleasures. Moments of humiliation or situations in which we were ridiculed or made to feel small come back to us much more frequently and with a larger emotional force than the moments in which we were admired or looked up to. Experiences of suffering, especially psychological suffering, create deep grooves in our psyche, drawing attention to themselves quite mechanically and frequently. Nations can be attached to their past humiliations and sufferings, perpetuating a sense of victimization from generation to generation. No wonder that, among many other definitions of yoga in the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna says that “Yoga is breaking the bond with suffering” (Bhagavad Gita 6:23).

Freedom from the whole domain of like-dislike, and pleasure-pain is a very great freedom. Then we do what needs to be done, whether we like it or not. It is possible to say that the whole meaning of the exquisite symbol of the cross for a serious Christian lies precisely in this: even if something is disagreeable or unpleasant or will produce pain, if it is necessary according to a higher understanding, then one would embrace the suffering intentionally and submit oneself to the right action. The outstanding example of this is from Christ himself. On the eve of his crucifixion, he prayed to God in the Garden of Gethsemane,

“Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Yet not my will but thine be done” (Mark 14:36). Another hindrance to samadhi is abhinivesha. This is sometimes translated as ‘a wish to continue living,’ but it is closer to ‘a wish to preserve the status quo.’ Abhinivesha is what is technically called ‘inertia’ in physics, as in Newton’s First Law of Motion (also called the Law of Inertia) according to which a body continues in a state of rest or of motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force. Abhinivesha is the wish for continuity of any state and any situation, because it is known. We fear the unknown and therefore we fear change which may lead to the unknown. In fact, this fear results from an attachment to the known, simply because how can the unknown, if it is truly unknown, produce fear or pleasure? In Phaedo, one of the dialogues of Plato, there is a scene in which Socrates has been given hemlock to drink and he is about to die. Some of his disciples are quite understandably very sad and are crying. Socrates says to them, “You are behaving as if you know what happens after death. And furthermore, as if you know that what happens after death is worse than what happens before death. As for myself, since I do not know, therefore I am free.”

Freedom from abhinivesha, from the wish to continue the known, is a dying to the self, or a dying to the world, or freedom from the self as mentioned earlier. It has often been said by the sages that only when we are willing and able to die to our old self, can we be born into a new vision and a new life. There is a cogent remark of St. Paul: “I die daily” (1 Corinthians 15:31). A profound saying of an ancient Sufi master, echoed in so much of sacred literature, is “If you die before you die, then you do not die when you die.”

What is needed is a dying to the old self, to allow a new birth, a spiritual birth. Dying daily is a spiritual practice—a regaining of a sort of innocence, which is quite different from ignorance, akin to openness and humility. It is an active unknowing; not achieved but needing to be renewed again and again. All serious meditation is a practice of dying to the ordinary self. If we allow ourselves the luxury of not knowing, and if we are not completely full of ourselves, we can hear the subtle whispers under the noises of the world outside and inside ourselves. A great sage, Sri Anirvan, said that the whole world is like a big bazaar in which everyone is shouting at the top of their voice wanting to make their little bargain. A recognition of this fact can invite us to a true metanoia, a turning around, to a new way of being. Otherwise, abhinivesha, the wish which maintains the status quo, persists.

This wish for continuity is rooted in a search for security and for permanence. Abhinivesha, the wish to hold on to the past, keeps us in the momentum of time. Being present from moment to moment requires a freedom from abhinivesha, and that freedom brings us to a radiant presence where we can be free of the fear of dying or of living.

Patanjali says, “These subtle kleshas can be overcome by pratiprasava--reversing the natural flow and returning to the source. Their effects can be reduced by meditation” (Yoga Sutras 2.10-11). Pratiprasava, the reversal of the natural flow, is required. It is the reversal of the natural outward tendencies of creation. Since the usual tendency of the whole of creation, therefore also of our mind, is outward, in order to move towards the center a reversal is needed, a turning around, a metanoia.

It is also possible to say that the spiritual practice of yoga, although opposed to the lower nature (or animal nature) in human beings, is in harmony with our higher nature (or spiritual nature). What we ordinarily regard as natural is what is usual and habitual with us. Our automatic habitual postures, thoughts, and feelings are manifestations of our ordinary state of consciousness, of a state of sleep or of mechanicality. It is through an impartial self-study (svadhyaya) that we become aware of the enormous strength of these tendencies which we need to struggle against as a part of self-discipline (tapas). We can appreciate the force of the tendencies of our lower ordinary nature during meditation where the distracted nature of our mind which runs after one association and then another is obvious. As we persist in practice (abhyasa), we can gradually acquire an attitude of detachment (vairagya) towards these distractions. As we identify ourselves less and less with these tendencies, realizing that they do not represent our real identity, we can become freer and freer of them. The force of the kleshas can diminish in meditation as we practice dying to our ordinary, habitual self, and orient ourselves to deeper aspects of our being.

-------------------------------------------

1 Please see R. Ravindra, The Wisdom of Patañjali’s yoga Sutras: A New Translation and Guide, Morning Light Press, Sandpoint, Idaho, USA, 2009.