Source: Extract from The Synthesis of Yoga - VOLUME 23 & 24 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. With due credit to Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, Pondicherry.

THERE are almost as many ways of arriving at Samadhi as there are different paths of Yoga. Indeed so great is the importance attached to it, not only as a supreme means of arriving at the highest consciousness, but as the very condition and status of that highest consciousness itself, in which alone it can be completely possessed and enjoyed while we are in the body, that certain disciplines of Yoga look as if they were only ways of arriving at Samadhi. All Yoga is in its nature an attempt and an arriving at unity with the Supreme, — unity with the being of the Supreme, unity with the consciousness of the Supreme, unity with the bliss of the Supreme, — or, if we repudiate the idea of absolute unity, at least at some kind of union, even if it be only for the soul to live in one status and periphery of being with the Divine, salokya, or in a sort of indivisible proximity,samipya . This can only be gained by rising to a higher level and intensity of consciousness than our ordinary mentality possesses. Samadhi, as we have seen, offers itself as the natural status of such a higher level and greater intensity. It assumes naturally a great importance in the Yoga of knowledge, because there it is the very principle of its method and its object to raise the mental consciousness into a clarity and concentrated power by which it can become entirely aware of, lost in, and identified with true being. But there are two great disciplines in which it becomes of an even greater importance. To these two systems, to Rajayoga and Hathayoga, we may as well now turn; for in spite of the wide difference of their methods from that of the path of knowledge, they have this same principle as their final justification. At the same time, it will not be necessary for us to do more than regard the spirit of their gradations in passing; for in a synthetic and integral Yoga they take a secondary importance; their aims have indeed to be included, but their methods can either altogether be dispensed with or used only for a preliminary or else a casual assistance.

Hathayoga is a powerful, but difficult and onerous system whose whole principle of action is founded on an intimate connection between the body and the soul. The body is the key, the body the secret both of bondage and of release, of animal weakness and of divine power, of the obscuration of the mind and soul and of their illumination, of subjection to pain and limitation and of self-mastery, of death and of immortality. The body is not to the Hathayogin a mere mass of living matter, but a mystic bridge between the spiritual and the physical being; one has even seen an ingenious exegete of the Hathayogic discipline explain the Vedantic symbol OM as a figure of this mystic human body. Although, however, he speaks always of the physical body and makes that the basis of his practices, he does not view it with the eye of the anatomist or physiologist, but describes and explains it in language which always looks back to the subtle body behind the physical system. In fact the whole aim of the Hathayogin may be summarised from our point of view, though he would not himself put it in that language, as an attempt by fixed scientific processes to give to the soul in the physical body the power, the light, the purity, the freedom, the ascending scales of spiritual experience which would naturally be open to it, if it dwelt here in the subtle and the developed causal vehicle.

To speak of the processes of Hathayoga as scientific may seem strange to those who associate the idea of science only with the superficial phenomena of the physical universe apart from all that is behind them; but they are equally based on definite experience of laws and their workings and give, when rightly practised, their well-tested results. In fact, Hathayoga is, in its own way, a system of knowledge; but while the proper Yoga of knowledge is a philosophy of being put into spiritual practice, a psychological system, this is a science of being, a psycho-physical system. Both produce physical, psychic and spiritual results; but because they stand at different poles of the same truth, to one the psycho-physical results are of small importance, the pure psychic and spiritual alone matter, and even the pure psychic are only accessories of the spiritual which absorb all the attention; in the other the physical is of immense importance, the psychical a considerable fruit, the spiritual the highest and consummating result, but it seems for a long time a thing postponed and remote, so great and absorbing is the attention which the body demands. It must not be forgotten, however, that both do arrive at the same end. Hathayoga, also, is a path, though by a long, difficult and meticulous movement, duhkham aptum, to the Supreme.

All Yoga proceeds in its method by three principles of practice; first, purification, that is to say, the removal of all aberrations, disorders, obstructions brought about by the mixed and irregular action of the energy of being in our physical, moral and mental system; secondly, concentration, that is to say, the bringing to its full intensity and the mastered and self-directed employment of that energy of being in us for a definite end; thirdly, liberation, that is to say, the release of our being from the narrow and painful knots of the individualised energy in a false and limited play, which at present are the law of our nature. The enjoyment of our liberated being which brings us into unity or union with the Supreme is the consummation; it is that for which Yoga is done. Three indispensable steps and the high, open and infinite levels to which they mount; and in all its practice Hathayoga keeps these in view.

The two main members of its physical discipline, to which the others are mere accessories, are asana, the habituating of the body to certain attitudes of immobility, and pranayama, the regulated direction and arrestation by exercises of breathing of the vital currents of energy in the body. The physical being is the instrument; but the physical being is made up of two elements, the physical and the vital, the body which is the apparent instrument and the basis, and the life energy, prana, which is the power and the real instrument. Both of these instruments are now our masters. We are subject to the body, we are subject to the life energy; it is only in a very limited degree that we can, though souls, though mental beings, at all pose as their masters. We are bound by a poor and limited physical nature, we are bound consequently by a poor and limited life-power which is all that the body can bear or to which it can give scope. Moreover, the action of each and both in us is subject not only to the narrowest limitations, but to a constant impurity, which renews itself every time it is rectified, and to all sorts of disorders, some of which are normal, a violent order, part of our ordinary physical life, others abnormal, its maladies and disturbances. With all this Hathayoga has to deal; all this it has to overcome; and it does it mainly by these two methods, complex and cumbrous in action, but simple in principle and effective.

The Hathayogic system of Asana has at its basis two profound ideas which bring with them many effective implications. The first is that of control by physical immobility, the second is that of power by immobility. The power of physical immobility is as important in Hathayoga as the power of mental immobility in the Yoga of knowledge, and for parallel reasons. To the mind unaccustomed to the deeper truths of our being and nature they would both seem to be a seeking after the listless passivity of inertia. The direct contrary is the truth; for Yogic passivity, whether of mind or body, is a condition of the greatest increase, possession and continence of energy. The normal activity of our minds is for the most part a disordered restlessness, full of waste and rapidly tentative expenditure of energy in which only a little is selected for the workings of the self-mastering will, — waste, be it understood, from this point of view, not that of universal Nature in which what is to us waste, serves the purposes of her economy. The activity of our bodies is a similar restlessness.

It is the sign of a constant inability of the body to hold even the limited life energy that enters into or is generated in it, and consequently of a general dissipation of this Pranic force with a quite subordinate element of ordered and well-economised activity. Moreover in the consequent interchange and balancing between the movement and interaction of the vital energies normally at work in the body and their interchange with those which act upon it from outside, whether the energies of others or of the general Pranic force variously active in the environment, there is a constant precarious balancing and adjustment which may at any moment go wrong. Every obstruction, every defect, every excess, every lesion creates impurities and disorders. Nature manages it all well enough for her own purposes, when left to herself; but the moment the blundering mind and will of the human being interfere with her habits and her vital instincts and intuitions, especially when they create false or artificial habits, a still more precarious order and frequent derangement become the rule of the being. Yet this interference is inevitable, since man lives not for the purposes of the vital Nature in him alone, but for higher purposes which she had not contemplated in her first balance and to which she has with difficulty to adjust her operations. Therefore the first necessity of a greater status or action is to get rid of this disordered restlessness, to still the activity and to regulate it. The Hathayogin has to bring about an abnormal poise of status and action of the body and the life energy, abnormal not in the direction of greater disorder, but of superiority and self-mastery.

The first object of the immobility of the Asana is to get rid of the restlessness imposed on the body and to force it to hold the Pranic energy instead of dissipating and squandering it. The experience in the practice of Asana is not that of a cessation and diminution of energy by inertia, but of a great increase, inpouring, circulation of force. The body, accustomed to work off superfluous energy by movement, is at first ill able to bear this increase and this retained inner action and betrays it by violent trembling’s; afterwards it habituates itself and, when the Asana is conquered, then it finds as much ease in the posture, however originally difficult or unusual to it, as in its easiest attitudes sedentary or recumbent. It becomes increasingly capable of holding whatever amount of increased vital energy is brought to bear upon it without needing to spill it out in movement, and this increase is so enormous as to seem illimitable, so that the body of the perfected Hathayogin is capable of feats of endurance, force, unfatigued expenditure of energy of which the normal physical powers of man at their highest would be incapable. For it is not only able to hold and retain this energy, but to bear its possession of the physical system and its more complete movement through it. The life energy, thus occupying and operating in a powerful, unified movement on the tranquil and passive body, freed from the restless balancing between the continent power and the contained, becomes a much greater and more effective force. In fact, it seems then rather to contain and possess and use the body than to be contained, possessed and used by it, — just as the restless active mind seems to seize on and use irregularly and imperfectly whatever spiritual force comes into it, but the tranquillised mind is held, possessed and used by the spiritual force.

The body, thus liberated from itself, purified from many of its disorders and irregularities, becomes, partly by Asana, completely by combined Asana and Pranayama, a perfected instrument. It is freed from its ready liability to fatigue; it acquires an immense power of health; its tendencies of decay, age and death are arrested. The Hathayogin even at an age advanced beyond the ordinary span maintains the unimpaired vigour, health and youth of the life in the body; even the appearance of physical youth is sustained for a longer time. He has a much greater power of longevity, and from his point of view, the body being the instrument; it is a matter of no small importance to preserve it long and to keep it for all that time free from impairing deficiencies. It is to be observed, also, that there are an enormous variety of Asanas in Hathayoga, running in their fullness beyond the number of eighty, some of them of the most complicated and difficult character. This variety serves partly to increase the results already noted, as well as to give a greater freedom and flexibility to the use of the body, but it serves also to alter the relation of the physical energy in the body to the earth energy with which it is related. The lightening of the heavy hold of the latter, of which the overcoming of fatigue is the first sign and the phenomenon of utthapana ¯ or partial levitation the last, is one result. The gross body begins to acquire something of the nature of the subtle body and to possess something of its relations with the life-energy; that becomes a greater force more powerfully felt and yet capable of a lighter and freer and more resolvable physical action, powers which culminate in the Hathayogic siddhis or extraordinary powers of garima, mahima, anima and laghima. Moreover, the life ceases to be entirely dependent on the action of the physical organs and functioning’s, such as the heart-beats and the breathing. These can in the end be suspended without cessation of or lesion to the life.

All this, however, the result in its perfection of Asana and Pranayama, is only a basic physical power and freedom. The higher use of Hathayoga depends more intimately on Pranayama. Asana deals more directly with the more material part of the physical totality, though here too it needs the aid of the other; Pranayama, starting from the physical immobility and self-holding which is secured by Asana, deals more directly with the subtler vital parts, the nervous system. This is done by various regulations of the breathing, starting from equality of respiration and inspiration and extending to the most diverse rhythmic regulations of both with an interval of inholding of the breath. In the end the keeping in of the breath, which has first to be done with some effort, and even its cessation become as easy and seem as natural as the constant taking in and throwing out which is its normal action. But the first objects of the Pranayama are to purify the nervous system, to circulate the life-energy through all the nerves without obstruction, disorder or irregularity, and to acquire a complete control of its functioning’s, so that the mind and will of the soul inhabiting the body may be no longer subject to the body or life or their combined limitations. The power of these exercises of breathing to bring about a purified and unobstructed state of the nervous system is a known and well-established fact of our physiology. It helps also to clear the physical system, but is not entirely effective at first on all its canals and openings; therefore the Hathayogin uses supplementary physical methods for clearing them out regularly of all their accumulations. The combination of these with Asana, — particular Asanas have even an effect in destroying particular diseases, — and with Pranayama maintains perfectly the health of the body. But the principal gain is that by this purification the vital energy can be directed anywhere, to any part of the body and in any way or with any rhythm of its movement.

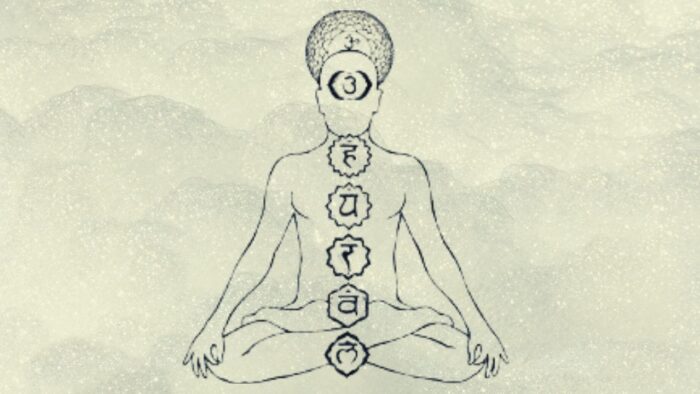

The mere function of breathing into and out of the lungs is only the most sensible, outward and seizable movement of the Prana, the Breath of Life in our physical system. The Prana has according to Yogic science a fivefold movement pervading all the nervous system and the whole material body and determining all its functioning’s. The Hathayogin seizes on the outward movement of respiration as a sort of key which opens to him the control of all these five powers of the Prana. He becomes sensibly aware of their inner operations, mentally conscious of his whole physical life and action. He is able to direct the Prana through all the nadis or nerve-channels of his system. He becomes aware of its action in the six cakras or ganglionic centres of the nervous system, and is able to open it up in each beyond its present limited, habitual and mechanical workings. He gets, in short, a perfect control of the life in the body in its most subtle nervous as well as in its grossest physical aspects, even over that in it which is at present involuntary and out of the reach of our observing consciousness and will. Thus a complete mastery of the body and the life and a free and effective use of them established upon a purification of their workings is founded as a basis for the higher aims of Hathayoga

All this, however, is still a mere basis, the outward and inward physical conditions of the two instruments used by Hathayoga. There still remains the more important matter of the psychical and spiritual effects to which they can be turned. This depends on the connection between the body and the mind and spirit and between the gross and the subtle body on which the system of Hathayoga takes its stand. Here it comes into line with Rajayoga, and a point is reached at which a transition from the one to the other can be made.