[Inner Work Through Yoga (IWTY) is one of the Yoga-based offerings developed by Raghu Anantanarayan, founder, Ritambhara that brings the wisdom of Yoga Sutra in a contemporary and contemplative way. It invites participants to engage with the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali in a self-reflective manner and see how it applies to one’s own life, actions, relationships and choices. Participants are encouraged to look at each sutra as a mirror to show something deeper about oneself, thereby making the sutra relevant to them. This ensures that the sutra does not become an injunction (rule) to follow, but instead opens up an enquiry for oneself. Here is the second and final part of the article, continued from last week - Part 1]

The process in a nutshell

The identity of the person or 'asmita' can thus be experienced at two levels. One at the manifest action level, and the other as a quintessential 'code' that is held deep within. The code is like the seed and the action patterns are the various possible branches that the unfolding action can choose to manifest through. Abhinivesha is the energy or Prana that is trapped within these patterns. It acts to preserve these patterns and codes. These patterns and codes are thus a pre-conditioned form that the abhnivesha energises. Any danger / threat to these forms is experienced as a threat to the self, the drk shakti. Abhinivesha keeps the asmita alive and active. Thus the darshana shakti which is the concretised matter (comprising of the mind, senses and body patterns) seems to have life and action.

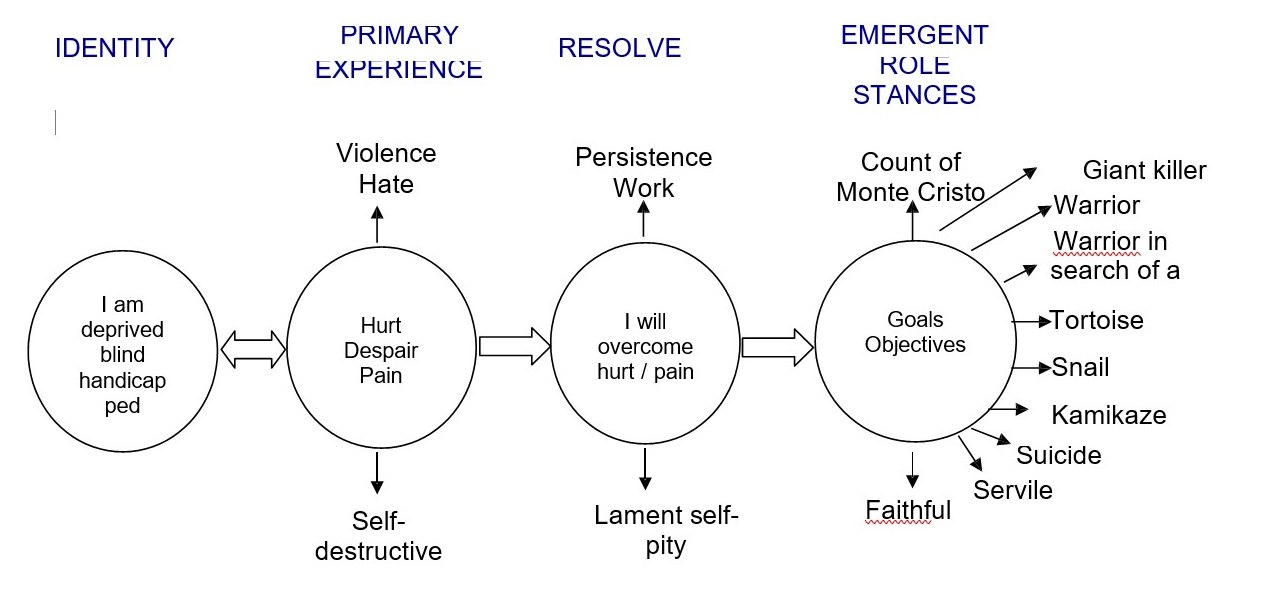

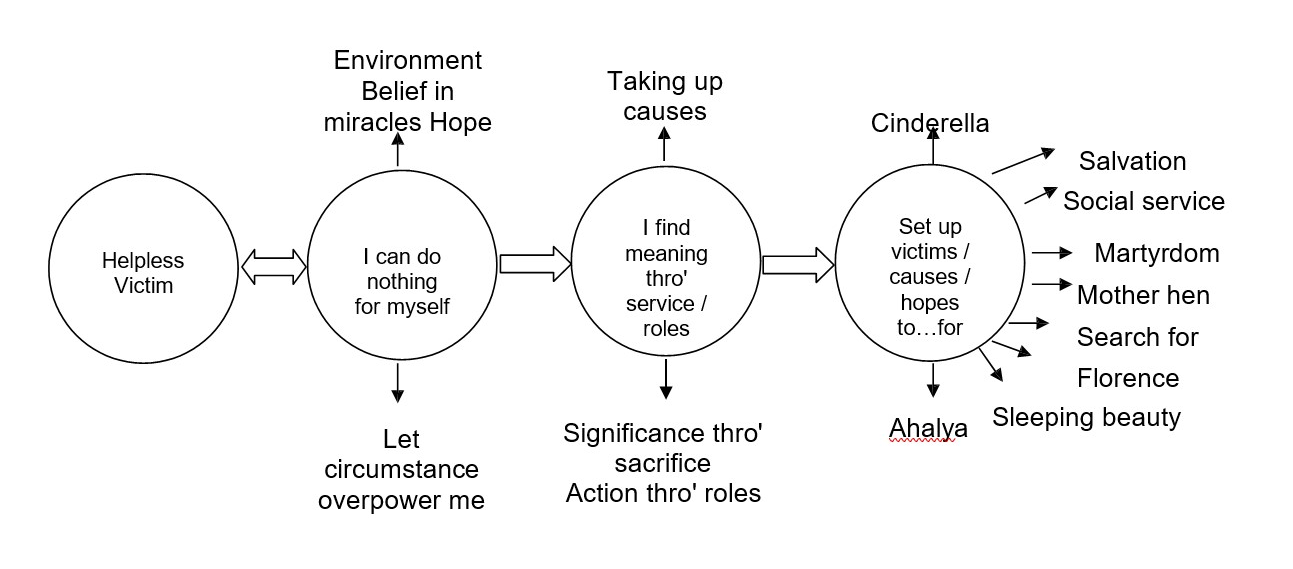

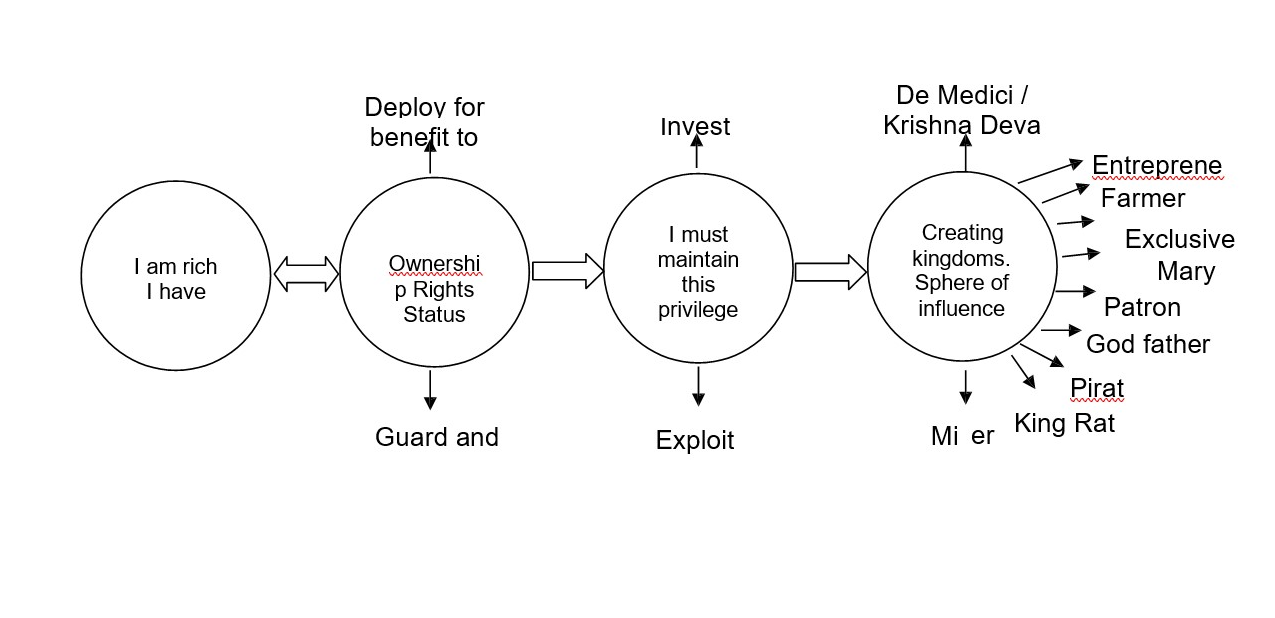

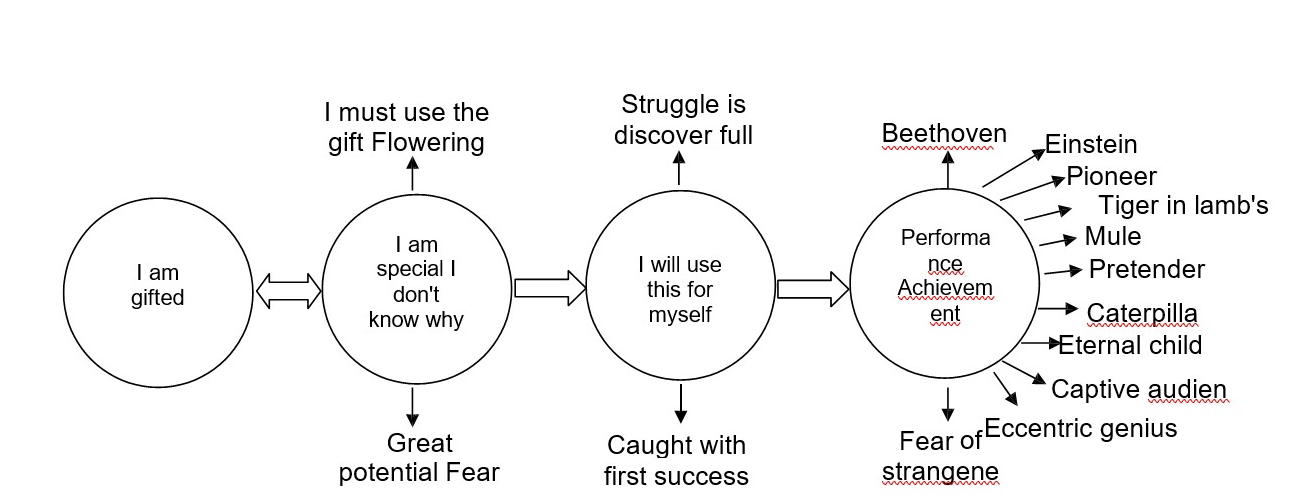

A graphic representation of four typical stances that emerged during the group explorations are given below :

Identities and role stances held by other participants in the group were of "The helpless victim", "The privileged" and "The gifted". The processes by which the identities and role stances are formed and gel into a pattern can be viewed in the same way as the one detailed above.

The resolution

Sutras IV 3/4/6 of the Yoga Sutra says that a new movement, one that is not locked into these patterns can be obtained. The process is neither an external imposition – nor is it through more external inputs. These can only cause temporary change.

The analogy given is that of a tree. The farmer gets sweet fruit not by pouring sugar and honey in the roots but through proper nourishment. The seed contains the quality of the tree and its fruit. This can be helped to grow to its fullest potential at best. Barriers to its realising its greater potential can be removed. A mind that is caught up in an identity and in set patterns of action alternatives is not free to develop to its fullest potential. This then becomes a barrier. The sutras therefore state that change at the levels of these deeply held identities leads to lasting change in the mind and behaviour of the person. When tendencies and patterns of the mind are carefully observed, the mind can be freed from the tyranny of the patterns. The identity is unlocked. The person does not see himself in terms such as "I am blind" or "I am handicapped". He experiences his personhood; the somatic components of the concretised mind also loosen their hold on the person. Psychosomatic stress is relieved. With this balance between the enquiry into the pressures of the psyche and a sensitivity and ability to work with the soma, the individual's development will have a flow.

The Sankhya Framework

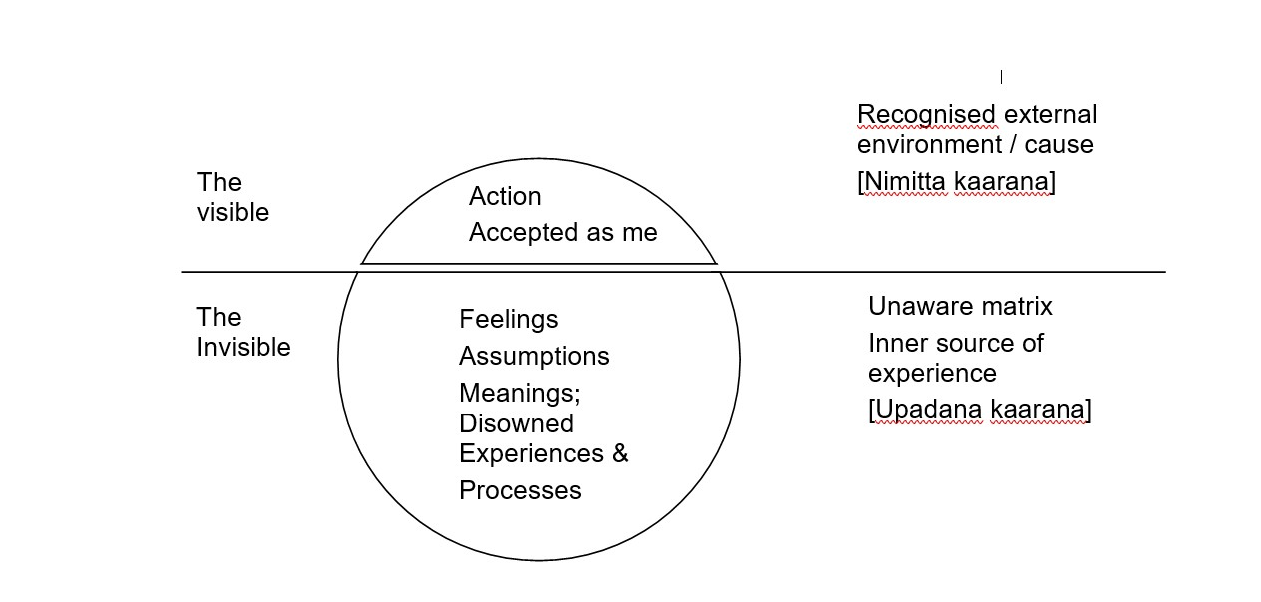

The Sankya Karika provides a model that describes this phenomenon with great clarity. Sankhya states that man is a composite of the visible, the invisible and the 'seer' or the 'experiencer'. The ability to understand deeply the influence of each of these on ones actions, perceptions or modes of living helps one to end the imprisonment in these patterns of samskaara.

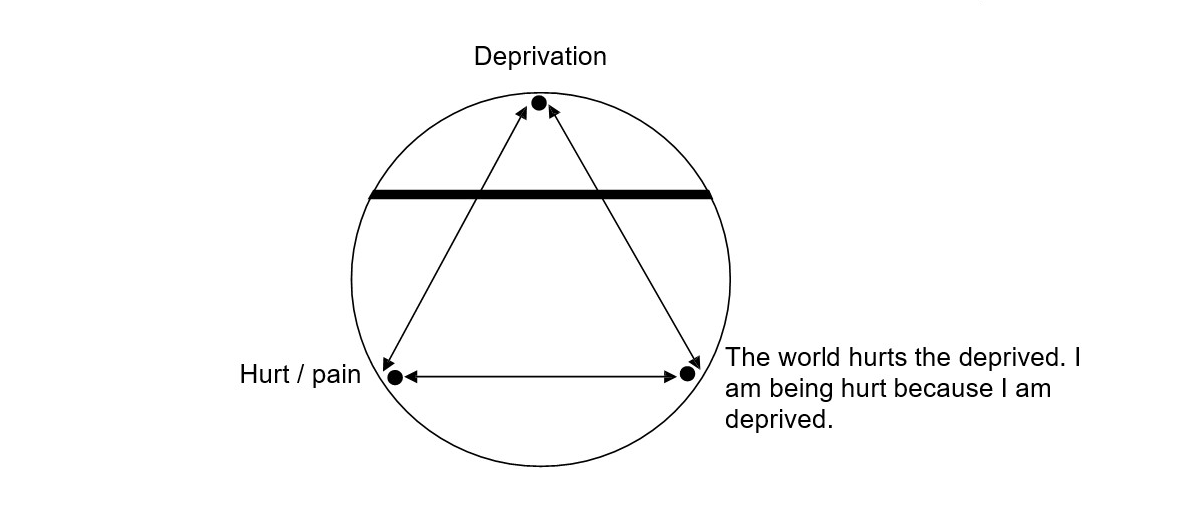

Man is like an ice berg. A very small part of him is visible, graspable and tangible. His feelings, the particular meanings he gives to an experience, the assumptions he holds about himself and the world are all invisible, unarticulated, disowned. He associates himself with the visible tangible part. He is therefore able to easily see that he is deprived or gifted in some way. Sankhya says that there are two important causes that converge to manifest an event, namely the external – or nimitta kaarana and the unmanifest and withheld matrix – the upaadaana kaarana. Relating an experience to the nimitta Kaarana is obvious and immediate. Thus it is easy to form the link: I am deprived – therefore the environment hurts me. This concretises into “I am blind therefore I am”! The means has now become the cause.

A unitary meaning is given to the experience of hurt and pain. Though the environment changes the meaning given is held unchanged.

The upadana karana or the unmanifest matrix is the source of the experience and the tangible only a means. This matrix is the unchanging part of the experience. Gradually a whole lot of assumptions grow around this conclusion. Unless the person can look into this matrix, re examine the assumptions and meanings he holds the patterns will not change, there is no release from sorrow – this is the fundamental thesis of Sankhya. The environment cannot be predicted or controlled. The ability of the person to experience his wholeness i.e., the manifest tangible differences, the commonness and universality of feelings and the meanings he has chosen to give to the experience (some of which he shares with others, some his own) is the key to be free of an endless repetition of the patterns. The source of this concretised mind can be looked at and changed. The external causes are beyond one's control.

The Yoga Methods for ending sorrow

Many methods have been suggested in the Yoga Sutras to attempt such enquiry. The conditions necessary for such an enquiry were created in the ancient times through the Gurukula system and the sagacity of the teacher. The Sutras describe the ambience in which such enquiry can take place as non-judgemental and motiveless. This is reminiscent of the mirror Brahma offered to Indira and Virochana in answer to their question "Who am I?"

Let us proceed to look at some of the suggestions described in the Yoga Sutra. A mind that is permeated with avidya is called a vishipta chitta: a mind that is unsteady, incapable of deep sustained enquiry. A person who acts from such a vishipta chitta manifests some of the following conditions:

- Vyaadhi – illness, disease, lack of physical wellbeing.

- Styaana – lack of motivation, stagnation, apathy, laziness

- Samshaya – doubt, uncertainty, inability to take decision

- Pramaada – carelessness, lack of foresight

- Aalasya – fatigue, listlessness, enervation

- Avirathi – high excitability, craving for sensuous stimulation

- Bhranti Darshana – lack of reality orientation, misunderstanding, distorted understanding

- Alabdha Bhumikatva – inability to priest, unable to lay a foundation.

- Anavasthitatva – regression, inability to consolidate.

These conditions also result in clearly recognisable symptoms:

- Dukha – psychological discomfort, feelings of misery

- Daurmanasya – helplessness, inability to start from oneself

- Angamejayatva – weakness of the body

- Shvasaprashvasa – unhealthy breathing patterns

The most clearly illustrated example of person in this state of mind is Arjuna at Kurukshetra. The Yoga Sutras go on to suggest several strategies to arrest these negative tendencies from snow balling and overcoming the person. The central idea in all these alternatives is Dhyaana- deep and persistent attentiveness to the arising and manifestation of action: how one perceives, makes meaning and chooses action. The common idea that runs through the many alternative courses of action suggested is that they aim to help one find from within himself an energy to start a new and positive movement. This positive action and the samskaara created will weaken and eventually remove the factors that sustain and nourish the negative. Thus the seeds of avidya are rendered inactive and are replaced by a new flowering. There is no dogma in the methods suggested. They must be used selectively and appropriately. Each suggestion is an alternative choice.

The first suggestion given is to take up an enquiry that will lead to an understanding of ‘what is’. The important consideration is that one takes up and sustains one line of thinking and explore it. Engaging repeatedly in this questioning would help the person quieten the mind and thus be able to understand himself from a greater depth.

The sutras then suggest that the person takes up a practice of Aasana and Praanaayaama. The effect of negative samskaara pervade the body as much as they do the psyche. It is, therefore, necessary to work with ones body and release from it the tensions and negative patterns. The person is thus capable of dealing with his situation in a more energetic manner, bodily and sensory distortions don't worsen the situation. The reduction of irritability achieved through these practices would also enable the person to be a little more considered in his responses.

Reflecting upon the quality of ones relatedness with others helps one to bring order in the mind. One is often caught in patterns of interaction with other people that

reinforce the distortions in oneself. Being able to link and establish friendship with people who create positive feelings in oneself; responding with the compassion that is evoked when one sees another in distress; experiencing and sharing joy in other people's happiness; being able to draw boundaries and de-link from associations that evoke negative patterns in oneself are the various suggestion made. Thus feelings of antagonism with other people, self centred behaviour, competitiveness and other such patterns that kindle the asmita, raaga, dvesha and abhinivesha in the person must be examined and ended. In the cases presented here the person with the identity of deprivation is helped to recognise that this attitude of servility to one who patronise him reinforces his negative identity. This recognition and a consequent ending of such a pattern also de-links him from an attitude and set of hopes and actions that sustain his lack of self-worth.

Gaining insight and understanding into the relationship between ones senses and the processes by which it links with objects leads to tranquillity. The experiencing of the world that goes on continually from the point of birth is mediated by the senses; such experiencing leads to an understanding of the world but also conditions and limits the senses. By getting in touch with ones inner processes one can gradually end conditioned patterns of response, craving, aversions and the like. The senses thus become finely tuned and sensitive instruments that can now perceive the true nature of the world. Let us look into the action of hearing to illustrate this. The sound, the meanings, ideas, associations and the reality of the object all impinge together in the mind when one hears a word). The understanding of the process of listening would imply that one can have an insight into each of the following :

- The nature of sound

- The processes of the mind and how memory and past residue, associations inferences, conclusions etc., that are held in the upadana arise as a response to the word

- The nature and quality of the object as is

This understanding then releases one from a limited recognition of the word. One is not mortgaged to ones particular meanings. One has reduced the force of possession of ones ideas and their defence. One can now look at ones own experiences from many new perspectives, listen to and give space for other meanings. Without this inner release one gets locked into an unitary experience of the world and becomes prisoner to crystallised response patterns.

One experiences the force and movement of life within oneself only indirectly – through the action of the senses and body. It is, therefore, only natural that ones asmita is formed through these experiences. Through a process of questioning this idea of ones being one can experience the flow of life without limiting it to the

objects both gross and subtle that evoke responses from within the person. This experience knocks holes into the bottom of the "asmita". The life force having been touched or experienced without the mediating form or image ends the source of threat. Death and survival are not linked to the survival of the image nor is living seen as strengthening and projecting of the asmita. When the blind person experiences intensely other peoples interactions with him or his interactions with the world in their directness and simplicity shorn of all motives (both from himself and others) he experiences this flow and vibrancy of life. The hold that his deprivation and its consequences have on him gets diminished.

A very simple alternative suggested by the sutras is to seek contact with person or objects or environments that evoke quietness and tranquillity in oneself: music, nature, great saints, the writings of great teachers and their life experiences. The teaching stories of the Sufi and Zen masters are some examples. One often hears of great scientists having made startling discoveries not when they were pre- occupied with finding solutions but when they were playing music or taking a quiet morning walk in the woods.

The quality of one's sleep, the images of a dream, symbols and association that holds special significance to a person can be the windows to deep introspection. They often point a deeply held samskaaras, raaga or dvesha that one experiences without consciously acting them out in wakefulness. Being able to deeply explore the underlying web of feelings and impressions leads to great insights and understanding.

The next sutra takes this as a step further and recommends deep contemplation on any issue or process that appeals to the person. The word Dhyaana as used in the Yoga Sutra can be translated into the words contemplation or meditation if one is careful to understand the English words in their original sense. Contemplation, comes from the root word temple (Greek) which means a space in which to observe. Meditation means ‘to get the true measure of’. Dhyaana is defined in the sutras as the deepening of the process of Dhaarana. It is staying with or sustaining an enquiry for a long period of time without distractions. The true measure of the self is observed directly. Such an intense enquiry into the nature of ones inner space is said to "burn the seeds" of avidya. Thus the memories and impressions held in the mind loose the potential to distort perception or create pressures of raga, dvesha or abhinivesha.

These methods listed are not exhaustive but give a fair indication of the range and depth of the strategies used to change a vishipta chitta into a mind capable of ekaagrata or distortion free, one pointed enquiry.

Learning Yoga today

Today it is clearly impossible for many of us to go back to the Gurukula or retire into seclusion and pursue such enquiry for extended periods of time with the help of a teacher. Nor is it necessary. The experiential learning component of the process can be learnt through reflection and enquiry that are initiated in identity groups. The understanding of the patterns of the mind and identities held within comes about through a deep sustained exploration. The models presented here emerged through a 12-day group process (8 to 10 hours per day) with 13 participants. The hidden contents of the mind are uncovered slowly and layer-by- layer. An atmosphere of trust, acceptance and working together is created in the group. The emphasis is on the understanding and exploration of the participant into his own processes.

Looking into some of the deeply held patterns, assumptions and conclusions is often painful and threatening. The resistance to re-examine and re-experience the hurt or fear is the force that keeps one locked in old patterns. The person first discovers the patterns that he is locked into. His ability to examine other possible perceptions and perspectives, very much like turning a kaleidoscope around, helps him take the first step towards becoming free of old patterns. Understanding the resistance and finding within oneself the ability to break free of them is the next major step. Trying out alternative action stances and perspectives can be considered a fair indication of the persons discovery of freedom.

In my experience, this enquiry into oneself when linked with the practice of Asana and Pranayama helps a great deal in managing the somatic components of the mind set. With this balance between the enquiry into the pressures of the psyche and a sensitive ability to work with the soma, the individual’s development will have a flow and an integration.