Yoga in Daily Life

[Excerpted from Spiritual Roots of Yoga by Ravi Ravindra]

Renouncing all actions on Me,

Mindful of your inner self,

Without expectation and selfishness,

Struggle without agitation. (Bhagavad Gita 3.30)

Krishna invites us and enjoins us to make our daily life into a spiritual practice, a yoga. No one can be without action. Even if we simply lie down, doing nothing visible, we are still engaged in action. �Because no one can remain actionless even for a moment. Everyone is driven to action, helplessly indeed, by the forces of nature� (BG 3.05). Even if the body is still, the mind is in action, associating this with that, dreaming, desiring something, fearing something else. The question is not whether to act but how to act. Similarly, no one can avoid daily life; the question is not whether we should participate in daily life, but rather how to participate in this life we live daily.

What Is Daily Life?

All the actions we do routinely�sleeping, eating, washing, walking, sitting, standing, talking�are included in our daily life. And so are all the activities we engage in as a part of our jobs, professions, household routines and the like. These are not without their importance, but our inquiry here has less to do with the various kinds of activities and much more to do with the quality of the actor engaged in these activities� willingly or unwillingly, driven by nature or driven by the spirit� because our daily activities reflect the quality of our being.

When Krishna speaks to Arjuna about a person of steady wisdom (sthitapraj�a), Arjuna does not ask what sort of wonderful ideas such a person has or what the theology or philosophy of a person of steady wisdom is. He asks: �How does a person of steady wisdom, who is established in samadhi,

speak? How does he sit? How does he walk?� (BG 2:54).

Krishna�s answer is quite unambiguous: �A person of steady wisdom is one who has become free of all desires that prey upon the mind, and who is content and at peace. When unpleasant things do not disturb, nor pleasures beguile, when craving, fear, and anger have left, such a one is a sage of steady wisdom� (BG 2:55�56).

There is a Hasidic story, which is also echoed in Zen circles, that tells of a pupil who goes to the master not as much to hear a learned discourse than to see how the master ties his shoe laces, to see how the master lives. And in our daily life we walk, talk, sit, and tie our shoe laces. We express our understanding and we search for steady wisdom in the midst of these very activities.

When we hope to move away from daily life, what do we expect to escape from? Do we hope to escape from the ordinariness, the repeatability, and the predictability of our daily life? Do we wish for adventure, for something unexpected, for something that will surprise us�perhaps an unexpected gift or a guest or an event? There is much to be said for new impressions that can bring our mechanical routine into question. There is value in going to new places, meeting new people and new ideas. We are refreshed by the unexpected; something other than the usual comes alive in us, and we feel reinvigorated and rejuvenated. But many things are still the same. Even on the final ascent to Mount Everest there are elements of daily life. Certainly, in the monastery� which for some might seem like a release from daily life into a realm of spirituality�the activities of daily life are required. Many requirements, mostly to do with the general maintenance of our bodies and of our places of shelter, are the same or very similar everywhere.

I once met a monk in a Buddhist monastery in Thailand. He had the venerable traditional name of Nagasena. At that time, he had been a monk for nearly thirty years, as long as I had been a professor. We were instantly drawn to each other, and spent practically the whole night speaking together. He said to me, �You know, being a monk is a profession like any other. It has its ups and downs, its routine, its excitement, and its dullness. It is just like daily life.�

When we think of daily life as a dull affair, consisting of ordinary activities, we are referring to a level of the mind, to a level of awareness and of engagement, which is dull and humdrum. When we wish to be released from daily life, it is this level of life and engagement that we wish to escape. We wish to live with another level of engagement�one in which we are not bored, or dispersed; in which we are more alive to ourselves and to everything around us. Those who are freshly in love have no complaints about daily life. It is the lack of a love affair with life that makes everything stale and dull and uninteresting. We can be connected with the same quality of engagement while washing dishes in a kitchen or praying in a monastery on Mount Athos.

Another aspect of life that mitigates against our sense of freedom is that of reward and punishment. What we call daily life�especially as contrasted with a holiday, or with retired life�is the feeling of being constrained by reward and punishment, by the hope of gain or the fear of loss. So, we dream of another life�perhaps in a monastery or perhaps at a resort�where we will not be driven by gain or loss, or reward and punishment, or ambition and fear, at least not in the ordinary sense of gain or loss. In this dream, we seek a satisfaction of some subtler kind, a reward of heaven perhaps, or a gain for our soul, but nothing crass or materialistic.

The subtler part of ourselves feels overwhelmed by the excessive demands of worldly life or is disenchanted by the crudity of this life. However, what we wish to escape from in our ordinary life resides not as much in what we actually do as in the quality of engagement with it and the motivations underlying the activities. The dullness or ordinariness of daily life is not as much characterized by a particular type of activity as by an attitude toward it. In the midst of the most sacred presence or activity, we can be driven by fear or competitiveness.

It comes as a surprise to find in the gospels that in the very presence of the Christ, the disciples were competing as to who would sit on the right side of Christ in heaven and who would be farther away! The low level of daily life can intrude even when we are in the presence of the Sacred. In the very holy of holies we can think of self-advancement and self-importance.

What Is Our Life For?

However, we live our life�in a dull or an excited manner, or in some extraordinary way�the question as to why we live is always there. The three famous sights which Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha-to-be, saw�namely, an old person, a diseased person, and a dead body�are not so strange to most of us. There is hardly a person who has not seen all of these three sights. But for most of us, it does not create the sort of psychological revolution it did for Siddhartha Gautama. We are not deeply engaged by these sights. I saw the dead body of my older brother who died when he was much younger than I am now, and I was deeply moved. But it cannot be said that it left a permanent

revolution in my thinking or behavior or general engagement with life. We see people die, even loved ones, but we do not behave as if we too are going to die. We live in the body as if the body were permanent, not subject to death and decay, mistaking the vehicle for the passenger.

There is a story in the Mahabharata in which a celestial being, a Yaksha, asks the five Pandava brothers in turn, �What is the greatest mystery in the world?� The stakes are high. If they give an unacceptable answer and still attempt to take water from the lake, they will die. All the four younger brothers die and finally it is the oldest brother, Yudhishtra, the son of Dharma, whose response is found acceptable by the yaksha, who then revives all the dead brothers. The greatest mystery, according to the wise Yudhishtra as well as the yaksha, is that even when I see everyone around me die, I do not really believe that I myself am going to die.

There is nothing that Siddhartha saw and experienced that could not be experienced in our daily life. But we lack a vital engagement, a certain kind of intensity, and the sort of passion that he brought to his experience. For our daily life to be a practice leading to the Real, for it to be yoga, an intensity of

engagement is needed. There is no recipe for this, but there are stages. We will not seek to be engaged differently unless we become aware of the lack of intensity, of passion, and of meaning in our lives. This is the first requirement. With this recognition, I may begin to blame others or to expect that a change of the situation will make the difference I yearn for, but I need to realize that it is my own relationship with the world and my activities that need to change.

My life is not going to be lived by someone else; I must live it myself�it is my opportunity and my challenge.

Gradually, we can begin to recognize that everything is the way it is because there are large-scale forces�to which we subscribe, or which also operate as much inside ourselves as outside�and that these forces have brought us to where we now are. These forces, which are the forces of the status quo, are very large. We begin to understand not only that a radical transformation of our being is necessary but also that such a transformation is not easy, and that we are deeply addicted to the status quo even though we occasionally see the need to be otherwise. St. Paul speaks for all of us, �I cannot even understand my own actions. I do not do what I want to do but what I hate. What happens is that I do, not the good I will to do, but the evil I do not intend� (Romans 7:15, 19). Arjuna asks, �Krishna, what makes a person commit evil, against his own will, as if compelled by force?� (BG 3.36).

When we see the force that causes us to repeat ourselves mechanically, we are ready to turn to the part that yearns to be free of this and to undertake a practice. We become aware that deep down in ourselves there is a contradiction: there is a part that searches for the truth and wishes to emerge

into the light, but there is also a part which is quite willing�usually out of fear and ambition�to subscribe to the status quo and to stay in the dark. In Indian mythology, there is a story of the churning of the milky ocean for obtaining amrita, the elixir of Eternal Life. The antigods (daityas) and the gods (adityas) are always in conflict. Both of them wish to live forever and have supremacy. They both wish to obtain amrita. The daityas are children of Kashyapa (literally meaning �vision�) and Diti (meaning �limited�). The adityas have the same father, Kashyapa, but their mother is Aditi (�unlimited�, �vast�). Naturally, the beings of limited vision fight against the beings of vaster vision. Both of these types of being are also within each one of us, representing and strengthening our own downward and upward tendencies. As the myth goes on to say, Vishnu, the highest God, advises the adityas to undertake the churning of the milky ocean for the purpose of obtaining amrita, but he also tells them that they cannot succeed in this churning without involving their unruly cousins, the daityas. Daityas may not have the right vision, but they have enormous energy, and their force is needed for the difficult task of churning.

Both aspects of myself are needed for the requisite effort and striving required for churning the sea of consciousness to find what can lead to freedom from the ravages of time.

When we see our situation and we see the need for transformation, we see that we need the support of a practice of yoga, a way to become free of our usual and ordinary limited habits of mind, feeling, and body. Whatever else we might say about it, yoga involves the whole of ourselves�body, mind, and heart. In order to bring about a change, a merciless self-knowledge is necessary, a recognition of all our contradictions, fears, and wishes. For a true self-knowledge, we need to see ourselves in the midst of daily life. It is precisely where we are and where we can begin from. All our life is like a hologram: any little piece of it contains the whole and can reveal the whole. Our gestures, postures, tone of voice, behavior to animals or to neighbours�any of these is a fit subject for investigation and can reveal a great deal about our inner self.

In the shloka (verse) of the Bhagavad Gita that was quoted in the very beginning of this essay, we are advised to renounce all our actions to Krishna while being mindful of our deepest self. What is �Krishna� for us? One of the roots of the word �Krishna� in Sanskrit is karshati which means �that which draws�. �Krishna� is what ultimately draws us. So, each one of us must ask of ourselves, �What is my Krishna? What is my Ultimate Attractor? What do I love deep down, more than anything else?� We will discover a lack of unity in ourselves; there are at least two of me, in me: one attracted by Krishna and the other attracted by self-importance.

I came out alone on my way to my tryst.

But who is this that follows me in the silent dark?

I move aside to avoid his presence but I escape him not.

He makes the dust rise from the earth with his swagger;

He adds his loud voice to every word that I utter.

He is my own little self, my Lord, he knows no shame;

But I am ashamed to come to thy door in his company.

�Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali, poem 30

Only when we see the two in us can we see the need to struggle with the undisciplined parts of ourselves, so that they can be gradually brought to submit to those parts which have a vaster vision and which see clearly. When we can engage in the struggle willingly and mindfully, we can embark on a journey in which more and more of ourselves becomes integrated in yoga and

by yoga.

Thus, our ordinary daily life can become a spiritual practice, a true sanyasa, not by renouncing the world, but by renouncing worldliness. It is a form of dying to the world, which in effect is a form of dying to our self, to the usual self which is thoroughly entangled in the forces ruling the world, forces of reward and punishment, of fear and self- importance.

The question �How to live with a centered self, integrated by yoga, but at the same time without being self-centered?� becomes more and more interesting, more and more important. It has often been said by the sages that only when we are willing and able to die to our old self can we be born into a new vision and a new life.

� There is a profound saying of an ancient Sufi master, echoed in much of sacred literature, which says, �If you die before you die, then you do not die when you die.� Krishnamurti in a conversation about life after death said, �The real question is �Can I die while I am living? Can I die to all my collections�material, psychological, religious?� If you can die to all that, then you�ll find out what is there after death. Either there is nothing; absolutely nothing. Or there is something. But you cannot find out until you actually die while living.�

St. Paul had said �I die daily.� Dying daily is a spiritual practice�a regaining of a sort of innocence, which is quite different from ignorance, akin to openness and humility, an active unknowing. If I allow myself the luxury of not knowing, and if I am not completely full of myself, I can hear the subtle whispers under the noises of the world outside and inside myself. A contemporary sage in India, Sri Anirvan, remarked that the whole world is like a big bazaar in which everyone is shouting at the top of their voice wanting to make their little bargain. A recognition of this can invite us to true metanoia, a turning around, to a new way of being. Otherwise, the momentum of the status quo, abhinivesha in the terminology of Yoga Sutra of Patan?jali, persists. Only in moments of real seeing can an action of true vairagya, a disenchantment with the hold of the unreal on our heart, take place. Otherwise, as Wordsworth put it, �Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.�

When the Real calls us, we realize that our attention fluctuates and that we cannot stay attuned to the call for a long time. We begin to understand that we cannot aspire to the steady wisdom of which Krishna speaks without acquiring steady attention, free of all movements of the mind. Then the opening sutra in Patan?jali�s Yoga Sutra acquires a practical importance for us: �Yoga is stopping all movements of the mind� or �Yoga is cultivating steadiness of attention� (YS 1:2). Now we can begin the practice of yoga, as if for the first time.

All Action Is Yoga

All these stages are a progressive movement, not away from our ordinary daily life but toward an awakening to and a transformation of that daily life. In the usual situation, we live in a dreamy state of nishkarma kama, actionless desiring. The practice of yoga, as it is strongly emphasized by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, is for the sake of nishkama karma, purposive action without selfish desire. Then the ordinary daily life itself is transformed, because the person who is living it is different. The same cooking and dishwashing, the same lecturing or writing or putting the garbage out is now extraordinary.

All action, all life is yoga. Yoga is relevant here and now, whoever I am, and wherever I am. What I am will change, and I will occupy different places. Yoga is not one specific action, or one particular exercise, or a fixed point of view. Every action, thought or situation can be yoga if it helps to bring about an integration. Each chapter in the Bhagavad Gita ends with a colophon declaring it to be a yoga, including the first chapter, which is called �the yoga of Arjuna�s crisis.� In the moment of a crisis of conscience, in the midst of despair and a decision not to act resulting from his recognition of the conflict of dharmas at various levels, Arjuna turns to Krishna, who is seated in his heart, as his own highest self. Thus, begins Arjuna�s apprenticeship in yoga.

Krishna is also seated in our heart, and we too can begin our practice of yoga. Krishna enumerates many definitions of yoga and many characteristics of a yogi, both as a beginner as well as an accomplished practitioner, appropriate to the stage of development of the aspirant. A yogi renounces inaction, then renounces the fruits of action, and then is gradually able to abandon all action except that which is the fulfillment of the will of Krishna, the Highest Being. Yogis are progressively free of dualities such as like-dislike, attachment-revulsion, success-failure, sorrow-pleasure. They are freer and freer of partiality, of desire, fear and anger, selfishness and pride. A yogi takes recourse to buddhi, mindfulness, and more and more acquires a stability of attention which is not unhinged by whatever the theologians, philosophers, or scientists have said or what they will say (BG 2.49�54).

Yoga is work well done (BG 2.50); it is the breaking of an attachment to past suffering (BG 6.23), and it is everything that leads us to our Krishna, our Highest Attractor, the sole signifier of significance in our life. �Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever sacrifice you undertake, whatever charity you give, whatever efforts you make, do all that as an offering unto Me� (BG 9.27).

And Yoga Is No Action

After much searching, striving, effort, responsibilities, and action, there is the call to abandon all doing, a complete surrender to the Highest Being (BG 18.66). In this state of total attention, of pure awareness, a yogi does not decide to do this or that. Right and compassionate action is a natural outcome of this state. It is not a state of inaction, but of non-egoistic action. I do not do it, but it is done through me or in me. As the Tao te Ching says, �The sage does nothing, but nothing is left undone.� This recognition is expressed in another tradition, where Christ says, �I am not myself the source of the words I speak: it is the Father who dwells in me doing His own work� (John 14:10). Meister Eckhart: �What we receive in contemplation, we give out in love.� Reverting to the Bhagavad Gita, seeing that gunas act upon gunas, a yogi realizes that he does nothing at all (13.29).

There is a mystery here. Not the kind of mystery that can be solved by the discovery of a missing clue by some clever sleuthing. It is a mystery not because something is missing, but more because it is overfull. It cannot be solved by our usual rational mind, but we can contact a level of being�of body, mind, and heart�where it is dissolved. Solving this mystery, much as responding to a koan in Zen, is not a matter of articulating a published solution. In a breakthrough of consciousness another level of being is contacted. This other being is naturally reflected in the way we talk, stand, or walk. Uday Shankar, the greatest Indian dancer in the twentieth century, felt hesitant even toward the end of his life to perform the dance he called �the walk of the Buddha after his enlightenment.� Finally, he did dance it, as an offering, a summation of his entire life�s practice and understanding of dance, the yoga of his life.

The solution to the mystery of acting while doing nothing, or of doing nothing while engaged in vigorous action, is not to be found in this or that description. The solution is inherent in a fundamental transformation of consciousness. Daily life is not only the place of spiritual practice, it is the goal of all spiritual practice. We may understand something in a monastery or in a cave or behind a tree, but we must return to where the ordinary forces are at play and where we must have our action for the sake of the world. Even after he had seen the great form of the Godhead, a vision not vouchsafed to many in the history of the universe, Arjuna had to fight in the battle that ensued. Krishna said in the Mahabharata that the choice a person faces is not between war and lack of war, or struggle and lack of struggle. The only choice is between struggle at one level or at another. We need to struggle in our world, in our daily life, against our own egos. If we are free at our present level of existence, then we shall have to struggle at other levels. After all, even the angels or the devas have egos, and they too have to struggle. A real practice of yoga will not take us away from the battle in the world, from daily life. It will lead us to an understanding of how to be engaged in the battle and yet still be above it. This is what Krishna says about such yogis:

Engaged, but not identified,

Various forces of nature do not disturb them.

They know that this is all a play of forces.

They are firm, unshaken. (BG 14.23)

[Image credits : Dr. Lorenzo Cohen]

[Image credits : Dr. Lorenzo Cohen]

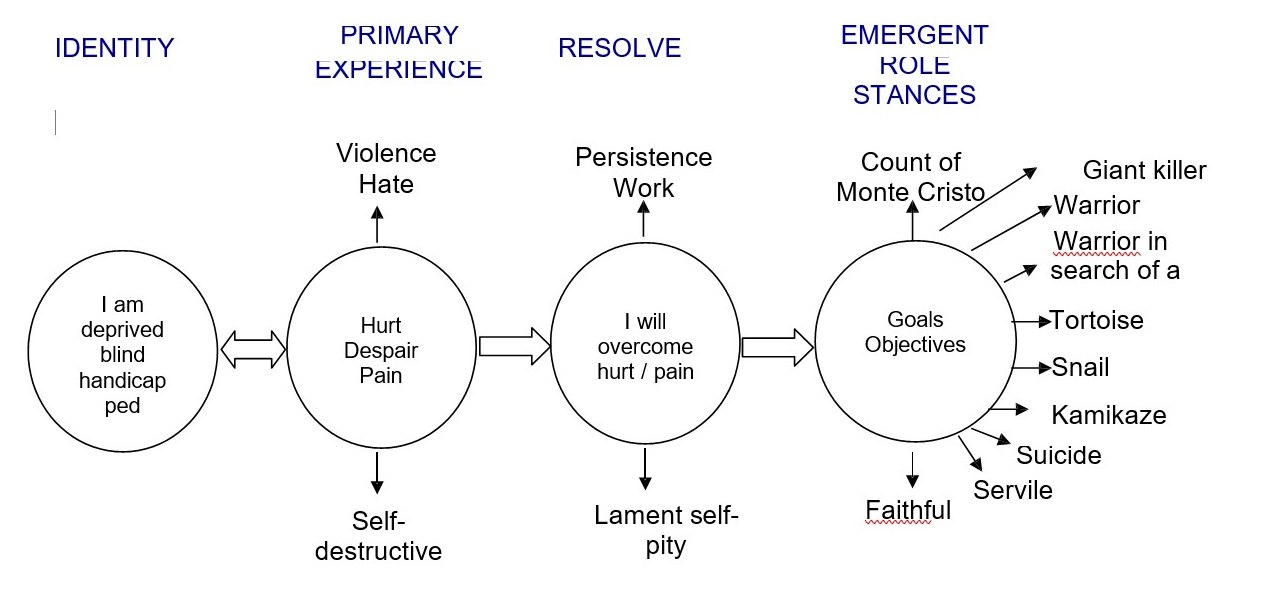

Dr Travis� current research includes the �Physiology of enlightenment that dawns through regular meditation practice and also the effects of listening to traditional chanting of the Veda and Vedic Literature.� The inevitable question that comes to one�s mind is how can neuroscience explain the genius of rishis like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi who intuited much of their knowledge?

Dr Travis� current research includes the �Physiology of enlightenment that dawns through regular meditation practice and also the effects of listening to traditional chanting of the Veda and Vedic Literature.� The inevitable question that comes to one�s mind is how can neuroscience explain the genius of rishis like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi who intuited much of their knowledge?